Back in 1983, Narre Warren neighbours Rob Wilson and Ray Bastin weren’t expecting to go head-to-head for their first of many council elections.

Both teachers and mates, they lived just five doors from each other on Sweeney Drive.

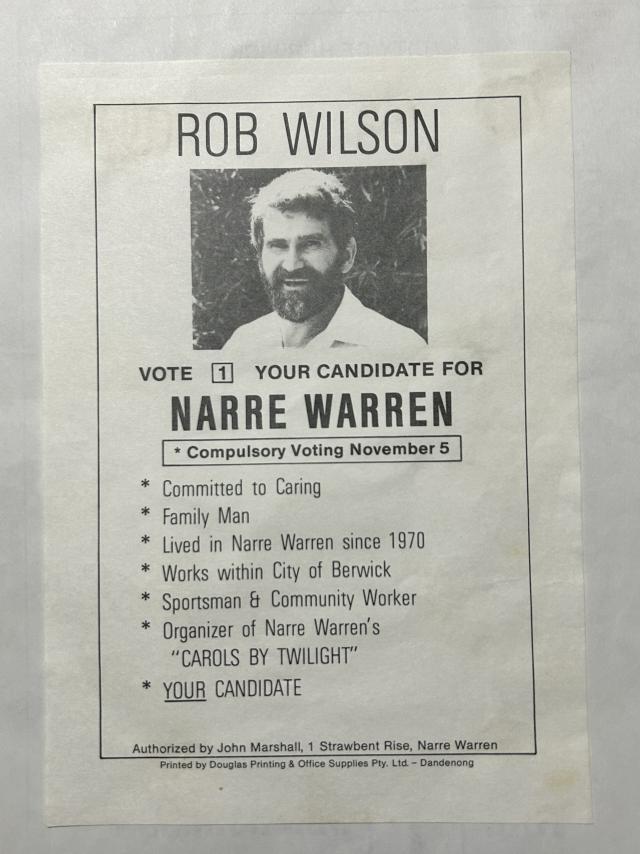

Active in his local church and the community, Wilson decided to run for the first time.

He recalls seeking Bastin’s help on his campaign for the then-City of Berwick polls.

“I had it in the back of my mind I’ll give it a run because I know that Ray is into politics.

“So I went down to see him and he said: ‘That’s funny because I’m running too’.”

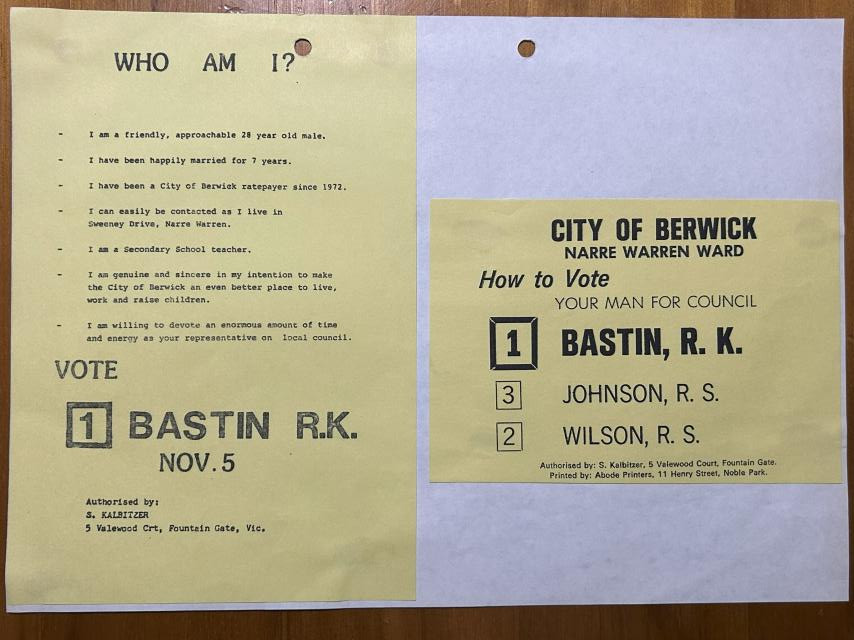

The then long-haired 28-year-old Bastin – fired up about sealing some local roads – had been thinking of getting Wilson to authorise his election material.

“That was my idea but you came down to my place and said you were running too,” Bastin said.

They ran independent campaigns but preferenced each other second on the how to vote cards.

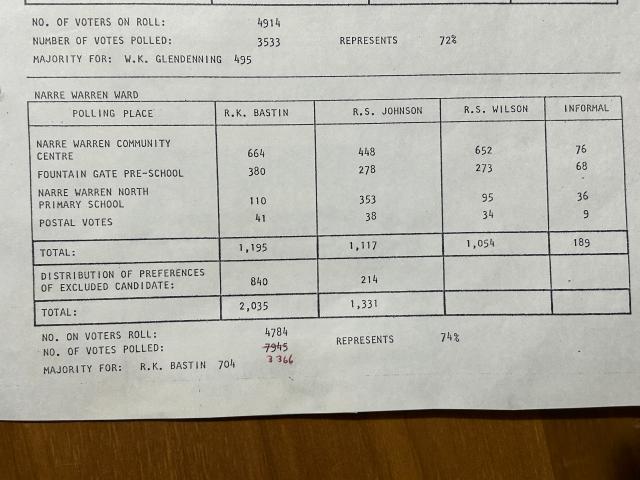

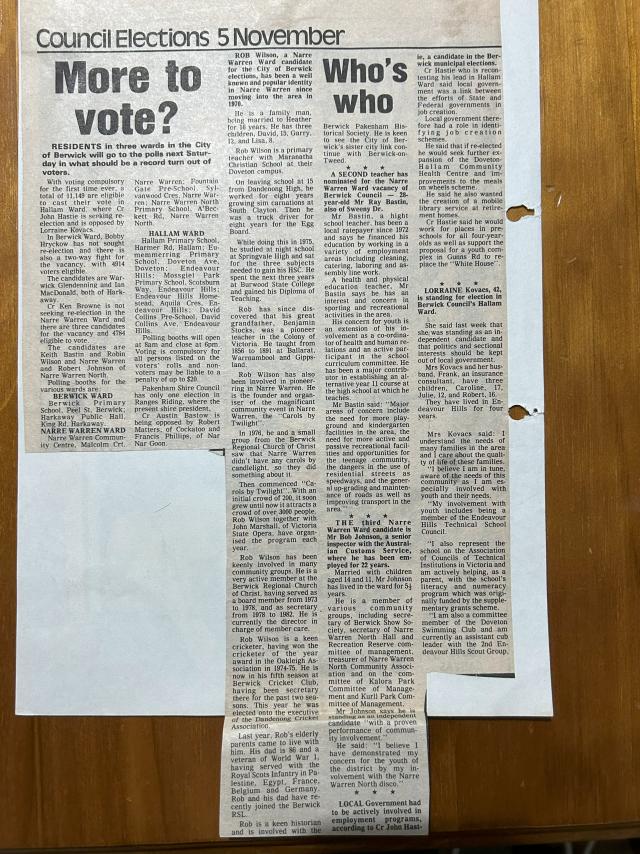

On election day – Saturday 5 November 1983 – it was Bastin who came out on top in an extraordinarily close three-way battle.

Bastin polled 1195 first preference votes, narrowly in front of Bob Johnson (1117) and Wilson (1054).

Garnering 80 per cent of Wilson’s preferences, Bastin ended up finishing 704 votes ahead of Johnson.

Wilson wryly notes that candidates were listed in alphabetical order on the ballot paper.

“When you look at the donkey vote, he (Bastin) scored it hands down.”

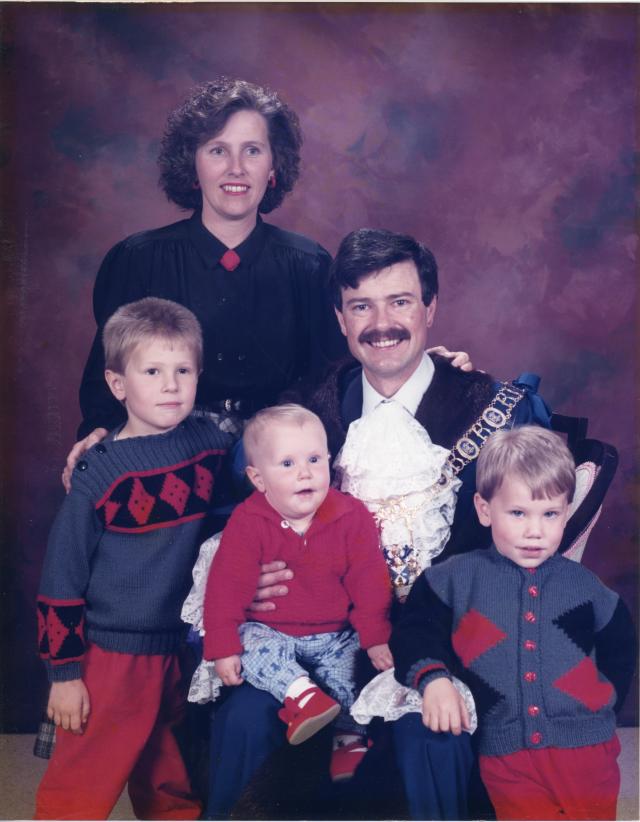

Both kicked onto long careers and mayoralty reigns on local council. Bastin served nine years with City of Berwick including as mayor in 1989-’90.

He topped every poll except in 1986 when he had two candidates against him, he says.

His name adorns the popular Ray Bastin Reserve, which is set for a $3 million revamp.

Meanwhile, Wilson won a seat on Berwick the next year. He served on both Berwick and Casey councils for 19 years including as Casey mayor.

Wilson had no political affiliations but Bastin never shied away from declaring he was a “Labor man”.

“Most of the time you’re dealing with local issues that have nothing to do with politics,” Bastin adds.

Council debate was mainly “pretty civil. But sometimes “vitriol” came with the job – not least when one of the councillors hurled a glass of milk in anger.

Bastin recalls the ratepayers “loved” him for opposing a proposed feed lot in Narre Warren South. But they were out to get him for supporting a residential drug rehab centre nearby.

“You’re always going to upset somebody but you just think what’s the best for the community.”

Wilson remembers his wife got a “threatening phone call” over the rehab issue. He named the culprit during the council meeting.

“Twelve months after he came and talked to me. And we’ve been the best of buddies since. How does that work?

“They are against the issue, but not necessarily against the person. And you can’t take it personally because you’re a public figure.”

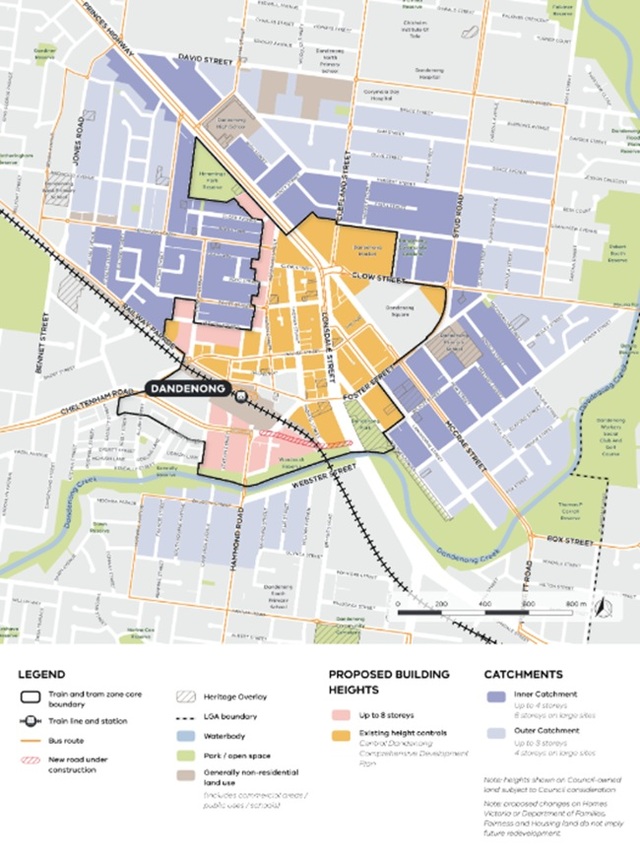

Council elections are set to return to Casey next year – the first since its councillors were sacked amid an IBAC Operation Sandon corruption probe in 2020.

Looking back, Wilson says he’s relieved that he lost his final council election in 2008.

“I always hated losing elections but I’m glad I wasn’t elected that year and becoming besmudged by the actions alleged by IBAC.”

He welcomes the prospect of elected councillors in charge, rather than State Government-appointed administrators.

“Because (councillors) care more about the city. They’re closer to what people are saying and thinking,” Wilson says.

“I hope we get some good people in. That’s the main thing.”