Illegal fruit-tree nets are taking a rising, deadly toll on grey-headed flying foxes, such as the colony in Doveton’s wetlands.

After a disturbing spate of flying-fox entanglements, The Conservation Regulator, Zoos Victoria, RSPCA Victoria, Wildlife Victoria and Animal Welfare Victoria have made a joint call for households to use wildlife-safe, compliant netting.

More than 110 flying-foxes have being reportedly tangled in illegal nets in the first six months of 2024.

This already exceeds the total entanglements during 2023.

In many cases, the ‘fruit bats’ are painfully wounded or killed.

A further 400-plus flying-fox pups were rescued and rehabilitated – with many suspected to have been separated from their mothers who were entangled in nets.

Numbers in the Myuna Wetlands colony in Doveton are in the normal 5000-10,000 range for winter, which is expected to triple in summer.

However Tamsyn Hogarth from Fly By Night bat clinic in Olinda is reeling from a worst-ever tally of casualties.

“We’ve seen over 100 bats needing rescue and care across Victoria in the past month. Plus an additional 30 rescues at the start of this month alone,” she posted in the first week of August.

Many are emaciated and starved from a lack of available native fruits and nectars.

Dwindling supply is also causing more flying foxes to be entangled in household fruit trees’ netting. This year’s extended fruit season up to May and June has also contributed.

She estimates that about 70 per cent of rescues don’t survive the horrific net wounds.

Often the victims can be suffering for several days before discovered and reported to rescuers.

A common, debilitating outcome is the die-back of wings, due to the mesh winding so tightly it constricts blood-flow.

Sometimes after the bat’s rescue, it takes several more days for the gory, gaping holes to emerge in their wings.

Bats freed by the public are sometimes too damaged to fly and are later found starving to death, Hogarth says.

“We can rehabilitate them for a few weeks but the damage is sometimes too much.”

Wings, fingers, thumbs and muscles can be deeply cut or as the bat frantically tries to free itself.

In some cases, lactating mothers with babies have chewed away at their own limbs in a desperate bid to free themselves.

Hogarth says there’s still a prolific amount of illegal nets being sold, particularly at “$2-shops”.

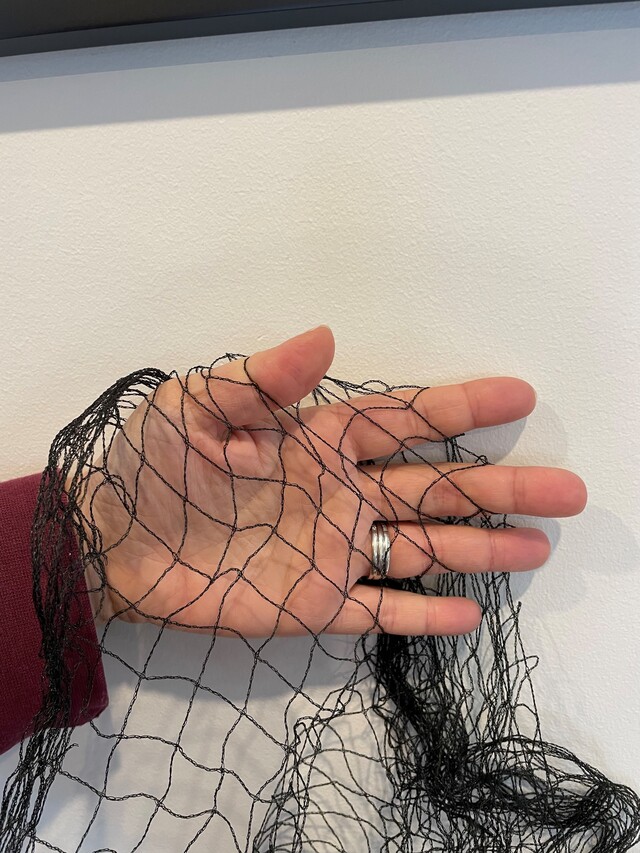

The injuries can often depend on the type of netting material. “If it’s black or green, we know it’s bad. The white nets are at least usually a softer net.”

A vulnerable species, the flying-foxes are often unfairly maligned, she says.

The bats play a vital role in pollinating native plants and ensuring some threatened flora’s survival.

Zoos Victoria acting chief executive Dr Sally Sherwen says the species fly thousands of kilometres in a year to search for food and pollinate a wide variety of plants, supporting important habitat for other animals like koalas and possums.

“By protecting the health and wellbeing of one species, we can help to ensure a future for an entire eco-system.”

Since late 2021, large mesh-size netting bigger than 5 millimetres by 5 millimetres has been illegal to use and sell in Victoria due to its tendency to injure wildlife.

On-the-spot fines of $395 to users and $790 to sellers apply, with penalties up to $2964 if prosecuted in court.

“We’re urging all household fruit growers to ensure they understand the law and have compliant fruit netting that protects both native wildlife and your household fruit trees,” Chief Conservation Regulator Kate Gavens said.

“A small change to your netting can make a big difference to the welfare of animals like grey-headed flying-foxes.”

The rule-of-thumb is if your finger can pass through the mess, then it’s too big.

Experts also encourage:

– white-coloured netting with a cross-weave design, which is more visible to animals at night

– tightly securing netting to a frame or tree trunk to prevent trapping terrestrial species.

– protecting selected branches with fruit bags or sleeves, rather than netting the whole tree.

Meanwhile, Casey Council have been implementing a management plan to preserve the Doveton colony.

This includes the formation of a Grey-headed Flying Fox (GHFF) stakeholder group, planned tree planting for future roosting habitat and to manage heat stress, ongoing weed management and monitoring by local wildlife carers and engagement with Bunurong Land Council on conservation works.

“The priority is ensuring the colony’s health through continued community engagement and education, including education on netting regulations and entanglements,” Casey sustainability and waste manager Michael Jansen says.

“Council is reviewing options to mitigate bat disturbance during high heat events and when pups are being reared through our bushland capital works program, which will be implemented in autumn/winter 2025.”

If a flying-fox is trapped in netting, do not attempt to handle it yourself. Call a wildlife rescuer on 136 186 or find one on wildlife.vic.gov.au/hfiw