Family violence can be dispelled within a generation – but it needs clear leadership, says the inspirational Hana Assafiri.

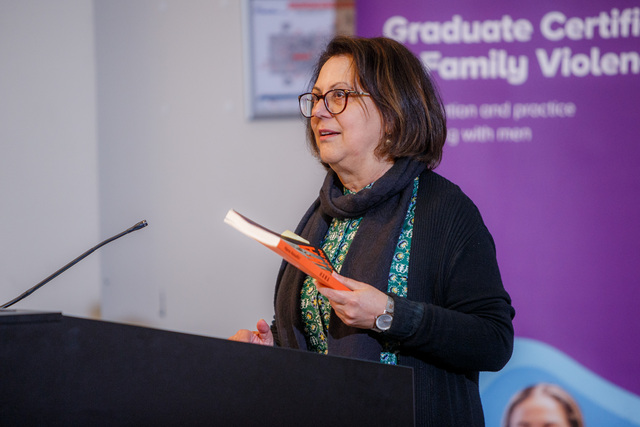

At the launch of Assafiri’s memoir Hana: The Audacity to be Free, she was part of a panel on family violence hosted by Wellsprings for Women on 3 July.

In her book, Assafiri traverses her life in migrating to Lebanon and back to Australia, as well as being family violence victim-survivor, support worker and the founder of the iconic Moroccan Soup Bar.

Assafiri called for “unequivocal” leadership and the end of “double-speak” about violence against women.

“We say we want to create this great utopian world where women would be safe.

“But we justify, condone and even reward behaviours that bully, coerce and violate women in practice.

“We see this play out in the highest office in the land. In Parliament House, how people abuse one another in Question Time. On the football field. In wars.

“These are all extensions of the same mindset.”

She told the forum that sadly for women the issue was “commonplace”. It was important to talk about the issue in a way that women could “imagine a way out”.

Back in the 1960s, her late Lebanese-born mother’s depression while in Melbourne showed that the services available didn’t “translate” for her.

The family, including a 5-year-old Assafiri, moved to Lebanon in an effort to help her mother.

One of the biggest differences that could be made was to make family violence services more accessible to everyone, she said.

Advertising campaigns on family violence were not as clear and pervasive as ‘Slip, slop, slap’ and 0.05 drink-driving campaigns.

The 1800 RESPECT hotline was little known, and should be replaced with simply calling triple-0.

She added why was it that women and children were taken away into refuges, rather than the perpetrators who could be put through treatment.

Co-panellist Sandra Maudier from Wellsprings told the audience not to be afraid to “ask the question” to suspected victims.

Dr Nimini Fernando backed up the point, advising people not to “give up” on offering support and to “travel with them”.

It took women about two years to act on violence against them at home, she said.

Wellsprings for Women chief executive Dalal Smiley said Assafiri’s story left her “gobsmacked”, despite knowing her in the family-violence sector since the 1980s.

“Sometimes just one of those issues can leave you with trauma for a lifetime. Yet she used her experience to make so much out of it.

“The simplicity of what she did in addressing family violence in women’s lives makes you realise how complicated we make things working in this sector.”

Assafiri left the family violence sector – frustrated by being unable to find safe accommodation for a fleeing woman and two children.

It led her to the Moroccan Soup Bar, a restaurant that she imagined would be a safe space for women.

She wanted to flip the notion of kitchens being a place of female subjugation, but a means to gain financial empowerment.

Common wisdom is that women on average leave an abuser seven times before exiting the last time. In 25 years at Moroccan Soup Bar, not one of the women returned to a violent partner.

“If you provide enduring, better options than the circumstances of violence, then women don’t need to go back.”

Safe and Equal board chair Maria Dimopoulos said the book was “inspiring as much as it is searingly painful” – breaking the silence on child sexual abuse and domestic violence.

She quoted from the prologue: “I wish for readers to recognise it’s in the cracks of vulnerability where we find our strength”.

Assafiri said she wanted to take the “shame and humiliation” away from those who endure abuse.

And to “place it where it belongs – to the perpetrators … and those who maintain the system of secrecy and silence.”

“Equally these events don’t define who you become – and nor should they ever.”

In a passage describing child sexual abuse, she left a page blank – “I tried to find the way to capture the essence … in the end you say nothing, you say everything,” she said.

However, on being told of the abuse, her mother attempted to avoid further humiliation by setting up Assafiri in an arranged marriage.

“I went from the hands of one abuser to another,” Assafiri told the audience. But it gave her the “capacity of lived experience”.

In her imagination and “secret escapes”, she found a “world of possibility”. Leaving the abusive marriage was “harrowing” but then formed the “possibility of being freed”.

She wished she had a book similar to her memoir as a companion during the “aloneness”.

“It’s in the absolute isolation – both culturally and individually – that’s where violence thrives. It takes people away from their social connections and networks.”

She hoped that in the pages, readers could see a “pathway of hope”.

Proceeds for the book Hira: The Audacity to be Free go to the First Nations women’s domestic violence service Djirra.